What happens when you take the design seriously instead of just the aesthetic.

There's a lazy version of this argument that goes: people love retro games because of nostalgia. Because they remind us of being young. Because the pixel art is charming. And sure, maybe that's part of it. But it doesn't explain why a teenager in 2026 who has never set foot in an arcade can pick up Breakout and immediately understand why it's fun.

These games work because the design is airtight. Not because the graphics are simple, not because the music is catchy, but because the underlying mechanics are so well tuned that they don't need anything else to carry them. Take away the cabinet art. Take away the CRT glow. Take away the nostalgia entirely. The games still hold.

Breakout works because the physics are satisfying. The angle at which the ball hits the paddle determines where it goes next. Every collision has a cause and an effect you can feel. There's a direct, physical logic to it that your brain understands before your conscious mind catches up. You don't need a tutorial. You don't need a story. You see the ball, you see the paddle, you see the bricks, and you know what to do.

Space Invaders works because the tension escalates perfectly. Not through a difficulty setting or a level number, but through the mechanics themselves. Fewer aliens means they move faster. The sound speeds up. Your cover deteriorates. The game gets harder because you're winning, which is a design idea so elegant that studios with hundred million dollar budgets still struggle to replicate it.

Frogger works because every death feels like your fault. Not unfair. Not random. You saw the car coming. You knew the turtle was about to dive. You jumped anyway. Frogger gives you complete information and dares you to act on it, and when you fail, you know exactly what you did wrong. That clarity of consequence is rare in any era of game design.

Pong works because competition is hardwired into us. Two paddles, one ball. The simplest possible competitive framework, and it's still compelling because the interaction between two human players creates infinite complexity from near zero mechanical complexity. Every rally is different because the other person is different.

These aren't accidents. These are design principles. And they don't expire.

Most "retro" games get this wrong. They copy the surface and ignore the structure.

You know the pattern. Pixel art. Chiptune soundtrack. Maybe a scanline filter. A title screen designed to look like a worn arcade flyer. And then underneath all that nostalgia dressing, a game that plays like every other mobile game: free to start, pay to continue, designed to addict rather than to satisfy.

The aesthetic of the arcade era is easy to reproduce. The design philosophy is harder. Because the design philosophy was built on constraints that no longer exist, and understanding those constraints matters.

Arcade games had to be learnable in thirty seconds because nobody was going to read a manual taped to the side of a cabinet. They had to be hard enough to eat quarters but fair enough that you blamed yourself, not the machine, when you lost. They had to offer depth through mastery rather than through content, because there wasn't room on the board for fifty levels and a branching storyline.

These constraints produced games where every element earned its place. Nothing was decorative. Nothing was filler. Every mechanic existed because it made the game better, and anything that didn't was cut, not because the designers were minimalists by philosophy, but because they literally could not afford to waste a single byte.

When a modern game puts a pixel art skin on a loot box economy and calls itself "retro," it has missed the point entirely. The thing that made those games great wasn't how they looked. It was how they played.

Bricks of Zai starts from a different premise. Instead of recreating how old games looked, it recreates how they thought.

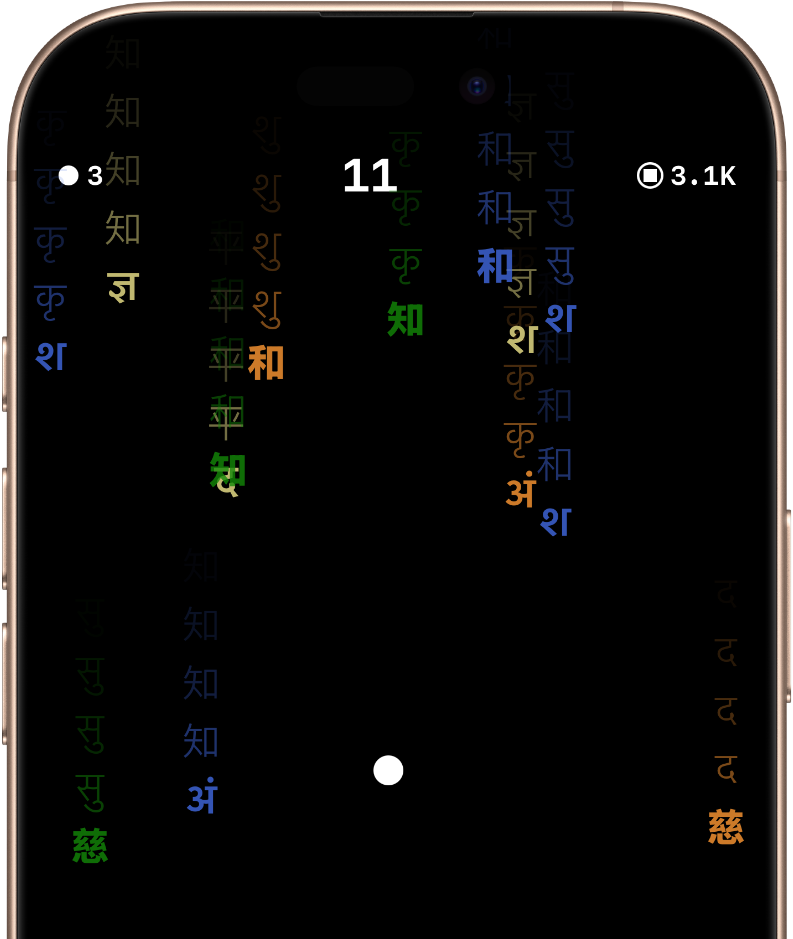

The framework is brick breaking, the genre Breakout invented in 1976. Ball, paddle, bricks. But Bricks of Zai has 19 game boards, and each one rebuilds the core mechanic of a different classic game within that brick breaking framework. Not as a reference. Not as a wink. As an actual playable reinterpretation that captures what made the original work.

The distinction matters. A reference says "hey, remember this?" A reinterpretation says "here's what this game was actually about, and here's what it feels like when you apply that idea to a different genre." One is a nostalgia trigger. The other is a design exercise. And the design exercise produces a much more interesting game.

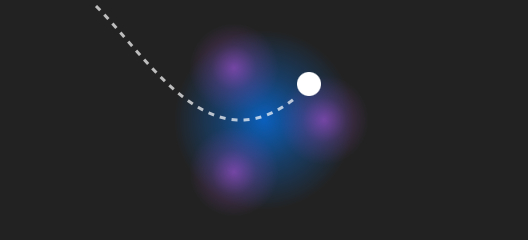

Consider what this means in practice. When the Gravity Wells board shifts gravitational fields to bend your ball's trajectory, it's not referencing a specific classic. It's applying the kind of physics manipulation that arcade designers would have loved to implement if they'd had the processing power. It takes the spirit of the era, the belief that a single mechanic change can create an entirely different experience, and runs with it.

The best way to understand what Bricks of Zai is doing is to look at how specific boards translate specific classics.

The original Centipede was brilliant because the game board evolved based on your actions. Every segment you shot became a mushroom. Every mushroom changed the centipede's path. The board you were playing on was the cumulative result of every decision you'd made. It was one of the first games where the environment was genuinely dynamic, not scripted.

The Centipede board in Bricks of Zai preserves this. The segmented centipede moves through mushroom obstacles, and every segment you hit with your ball drops a new mushroom. The playing field is constantly reshaping itself. The path the centipede takes on round one is different from round two because you've changed the terrain. Your past shots are literally the landscape you're navigating now. It's the same emergent complexity the original achieved, translated into a brick breaking context where the consequences of every collision are visible and permanent.

This board doesn't map to one specific classic, but it channels the spirit of every game that made physics the puzzle. Gravitational fields scattered across the board bend the trajectory of your ball in real time. The ball curves toward gravity sources, accelerates through them, slingshots around them. You can't just aim at a brick and fire. You have to aim at a point in space that the gravity will redirect your ball through on its way to the brick.

It's the kind of mechanic that changes how your brain processes the entire game. On the Classic board, you think in straight lines and angles. On Gravity Wells, you think in arcs and curves. Your intuition about where the ball will go has to completely recalibrate, and that recalibration, that moment when you start to feel the gravity instead of fighting it, is genuinely satisfying in a way that a simple difficulty increase never is.

Space Invaders was never really about shooting aliens. It was about the shrinking gap between the formation and the ground. Every moment you didn't clear a row, the threat got closer. The game's genius was that this pressure was visible. You could see your remaining margin. You could watch it disappear.

The Alien Landers board translates this exactly. The brick formation descends, and every volley brings it closer to your paddle. The board is spatially compressing, and the same panic that defined Space Invaders, the feeling that the walls are closing in because they literally are, drives the gameplay. You can't be passive. You can't let the ball bounce around randomly and hope for the best. You need to be deliberate, aggressive, targeted, because every wasted second costs you space you can't get back.

Quantum Reality is the most conceptually ambitious board. Bricks exist in superposition. The ball can quantum tunnel through barriers. Hitting one entangled brick affects its partner elsewhere on the board. The rules of physics, the rules that every other board teaches you to rely on, become unreliable.

This is a design idea that the arcade era couldn't have executed, but it grows from the same soil. The best arcade games always had at least one mechanic that kept you off balance, that prevented mastery from becoming autopilot. Pac Man had the ghosts switching between chase and scatter mode. Galaga had the boss capture. Centipede had the spider's random diagonal path. Quantum Reality takes that principle, the idea that a game needs controlled unpredictability to stay interesting, and pushes it further than an arcade designer in 1982 ever could.

Frogger was an observation game disguised as an action game. The cars and logs moved in fixed patterns. The game wasn't testing your reflexes so much as your patience and your ability to read traffic. The people who were good at Frogger didn't have faster thumbs. They had better pattern recognition.

Rush Hour brings that to brick breaking. Bricks move in lanes, each lane at a different speed. Your ball has to navigate through moving traffic to reach the targets. You watch the patterns. You time your shots. You wait for the gap. It rewards patience and observation the same way Frogger did, and it punishes the same impulse Frogger punished: jumping before you've actually looked.

There are plenty of retro game compilations on the App Store. Emulators, remakes, collections. They let you play the original games, or something close to them, on your phone. That's fine. That has its place.

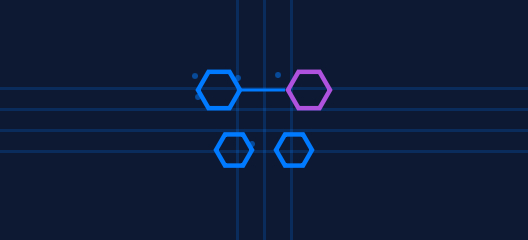

But Bricks of Zai is doing something structurally different. Instead of giving you nineteen separate games that each do one thing, it gives you one game that contains nineteen different ideas. And the shared framework, ball, paddle, bricks, is what makes the differences between boards feel so pronounced.

When you switch from the Pinball board to the Centipede board, the contrast is sharp because the input is the same. You're still controlling a paddle. You're still hitting a ball. But the way you think about that paddle and that ball is completely different. Pinball is reactive and chaotic. Centipede is strategic and cumulative. The shared framework makes the design differences legible in a way they wouldn't be if each board were a separate app with separate controls and separate visual languages.

It's the same reason a musician covering a song in a different genre can reveal things about the song that the original obscured. When you strip away everything except the core idea and rebuild it in a new context, you find out what the idea actually is. Bricks of Zai does this with game design. It takes the core idea of Space Invaders, of Frogger, of Donkey Kong, of Pong, strips it down to its essential mechanic, and rebuilds it inside a brick breaker. What survives that translation is the part that was always great.

Bricks of Zai is free on iPhone and iPad. Several boards are available from the start. Additional boards are unlockable with Zai coins that you earn through gameplay, not through your credit card.

There are no subscriptions. No energy systems. No ads between rounds. You play, you earn coins, you unlock boards. If that sounds refreshingly old school, it's because it is. The arcade model was always transactional in the most honest way possible: put in a quarter, play a game. Bricks of Zai is even more generous than that, since the initial boards cost nothing at all.

Your progress and purchases sync across devices through iCloud. Unlock a board on your iPhone, and it's there on your iPad. No account creation, no login, no friend codes. Just iCloud doing what iCloud does.

The game has 19 boards at launch: Classic, Fortress, Mountain, Diamond, Shields Up, One Way, Zai's Paddle, Zai's Turret, Gravity Wells, Harmony, Pinball, Alien Landers, Rush Hour, Spiders, Quantum Reality, Zero G Cookie Jar, Centipede, Under the Weather, and Barrel Blitz. Each one plays differently enough to feel like its own game.

The physical arcades are mostly gone. The few that remain are more museum than hangout, novelty destinations rather than places where teenagers spend their Saturdays. That's fine. The buildings were never the point.

The point was the games. The tight loops. The escalating difficulty. The "just one more try" pull that came from knowing the game was fair and you could do better. The design philosophy that said: every element earns its place, every mechanic serves the experience, and if the game isn't fun in the first ten seconds, no amount of content will save it.

That philosophy didn't die when the arcades closed. It just got harder to find. It got buried under free to play economies, progression systems designed by behavioral psychologists, and games that mistake content volume for quality. The craft is still out there, but you have to look for it.

Bricks of Zai is a game built by people who went looking. Nineteen boards, each one grounded in the design ideas that made the arcade era worth remembering. Not the pixel art. Not the nostalgia. The actual design. The mechanics that worked then and work now because good design doesn't have an expiration date.

It's on your phone. It's free. The games you grew up with are in there, rebuilt and waiting.